WHAT IS AN EMERGENCY FOOD NETWORK?

The term “emergency food network” describes a group of local, regional and state-wide social service agencies that work together to meet the short-term nutritional needs of food insecure households. Emergency food networks include such organizations as food banks, soup kitchens, food pantries, and homeless shelters that seek to meet the immediate supplemental food needs of people confronting various crises stemming from changes in the employment or health status of individual people to the effects of natural disasters or economic decline on populations living in a wide geographic area.

While emergencies are often viewed as something temporary, the social networks that coordinate and respond to these crises are permanently on call. Unfortunately for many people who do not command sufficient income to meet basic nutritional needs, daily life is shaped by vulnerability to these kinds of disastrous events. For roughly 300,000 people in West Virginia, the emergency food network provides immediate assistance at some point throughout the year.

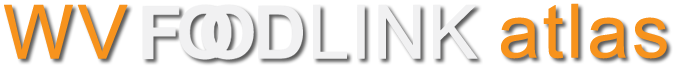

EMERGENCY FOOD NETWORK IN WV

The Emergency Food Network in West Virginia is comprised of two Food Banks, private non-profit organizations that aggregate and distribute food to over 600 affiliate food assistance charities. These include soup kitchens, family crisis centers, homeless shelters, day cares and neighborhood food pantries. In 2013 Mountaineer Food Bank and Facing Hunger Food Bank distributed 15 million pounds of food to 350,000 seniors, adults and children throughout all of West Virginia’s 55 counties.

This map illustrate the geographic reach of each Food Bank and the counties in which their service overlaps.

Food Banks staff 10 -15 full time workers in clerical, warehouse and trucking positions to oversee the daily logistics of collecting and moving food throughout the state with very little resources. Food Banks in a rural state like West Virginia face transportation and logistic barriers not faced by their urban counterparts across the country. These bring added costs and Food Banks in West Virginia have historically been significantly under funded. Currently, Food Banks are financially sustained through charitable donations, funds from The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) administered by the USDA through the WV Department of Agriculture , and revenue generated by local assistance agencies who purchase recovered food from Feeding America affiliated retailers.

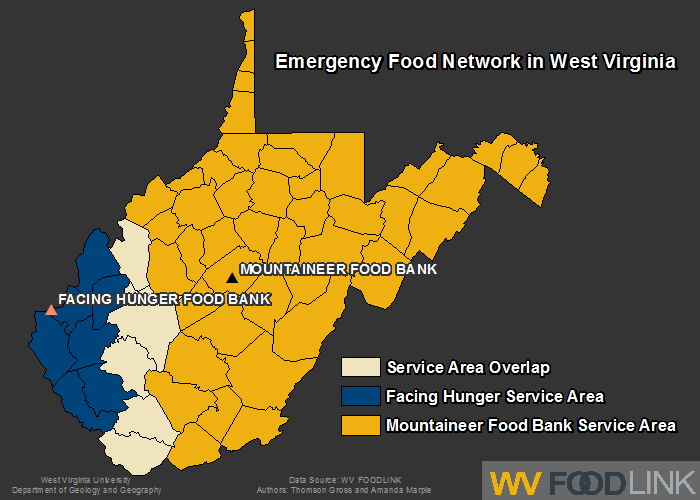

FACING HUNGER FOOD BANK SERVICE AREA

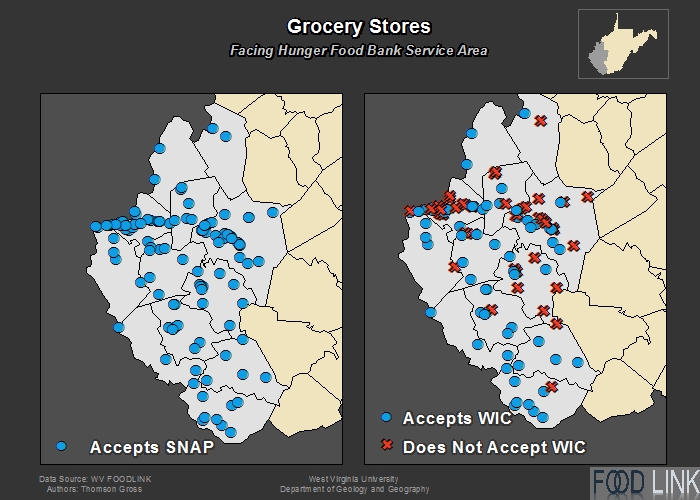

There are two food banks currently operating in West Virginia. Over the past year the research team at WV FOODLINK has partnered with the Facing Hunger Food Bank, located in Huntington, WV to collect data on the affiliated agencies within their service area. Facing Hunger Food Bank distributes food to 200 agencies in 18 counties in WV, KY and OH. WV FOODLINK began its partnership with Mountaineer Food Bank in Gassaway, WV more recently and because their service area is much larger the dataset is not yet complete.

As such the remaining maps in this section of the atlas draw on data collected in the Facing Hunger service area and represent agencies that are affiliated with that particular Food Bank either through USDA commodities distribution or the purchase (cost sharing) of donated foods through the Feeding America network. We must note that there are food assistance agencies not affiliated with the Food Bank through either program that do very important work everyday collecting food from other sources. For the time being, agencies are outside the scope of our research and as such are not represented in the Atlas.

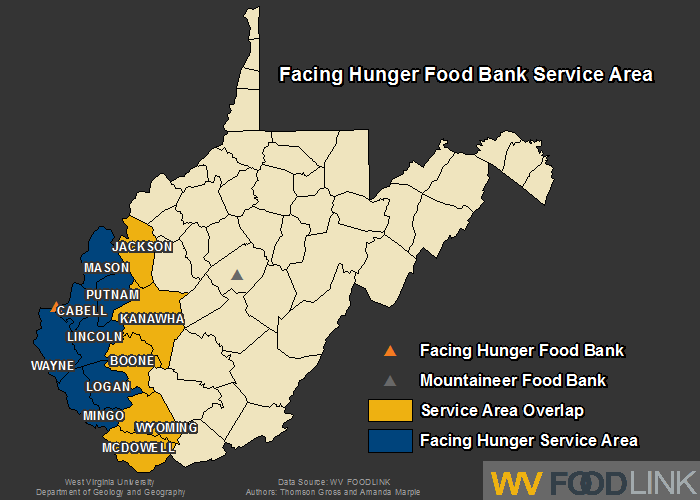

EMERGENCY FOOD SUPPLIERS

Food Banks serve the people of the West Virginia in two key ways. First, the Food Banks distribute USDA commodities from TEFAP . TEFAP foods are allocated to states from the USDA’s commodity purchasing program which warehouses excess agricultural products from US farmers and food processors. Secondly, the Food Banks also serve as a hub for donated and excess foods recovered from retailers and manufacturers affiliated with the Feeding America network.

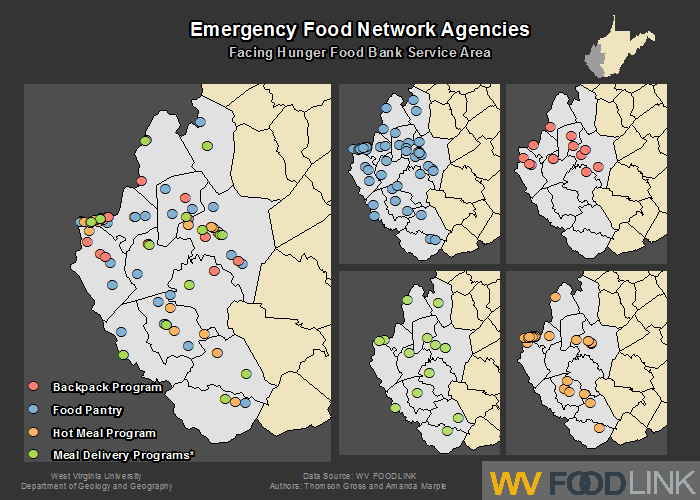

EMERGENCY FOOD NETWORK AGENCIES

Local Assistance Programs are the primary delivery services for public and private food donations. Common to all local food assistance programs is a deep sense of commitment to alleviating hunger. While size and service area may vary, each program involves a high level of organization, including fundraising, budgeting, food sourcing and delivery, volunteer management and reporting back to partners and funders. These complex entities are most always understaffed and highly dependent on their volunteer networks to continue providing services on a daily, weekly or monthly basis.

While we’ve organized local assistance programs into four broad categories each is highly unique addressing critical food needs differently in their community based on geographic contexts, the populations served and the staffing resources at their disposal.

Hot Meal Programs offer daily meals and require kitchen and service staff, while food Pantries are open less frequently to provide a three day supply of dry or canned goods, and refrigerated foods when available as well. Meal delivery programs work with volunteers to deliver hot meals to those stranded at home, often the elderly. Backpack programs are a supplement to school feeding programs, providing weekend nutrition to students who need it.

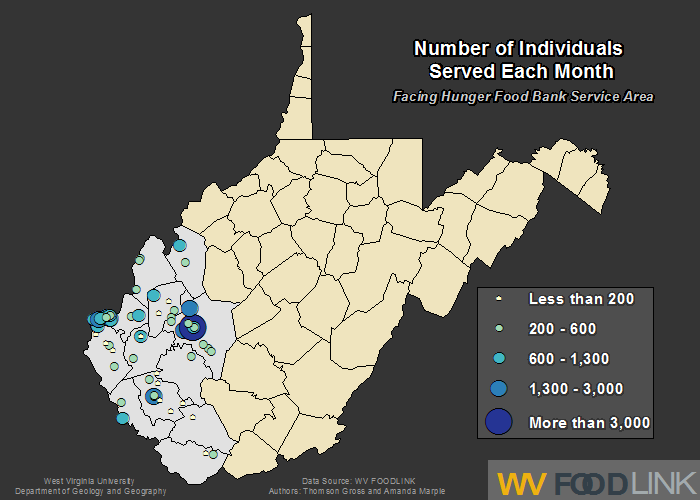

NUMBER OF INDIVIDUALS SERVED EACH MONTH

Each assistance agency is unique. The skills, physical capacity and personality of the staff, along with the material resources at their disposal often dictate the number individuals an agency is able to serve on a monthly basis. An urban hot meal program, by the nature of its daily routine serves many more people than a rural mission church food pantry. Of importance is the role that each agency plays in the wider food security safety net. The landscape of need is constantly changing, agencies are opening and closing all the time and this map is merely a static snapshot representing a monthly average at a particular moment in time.

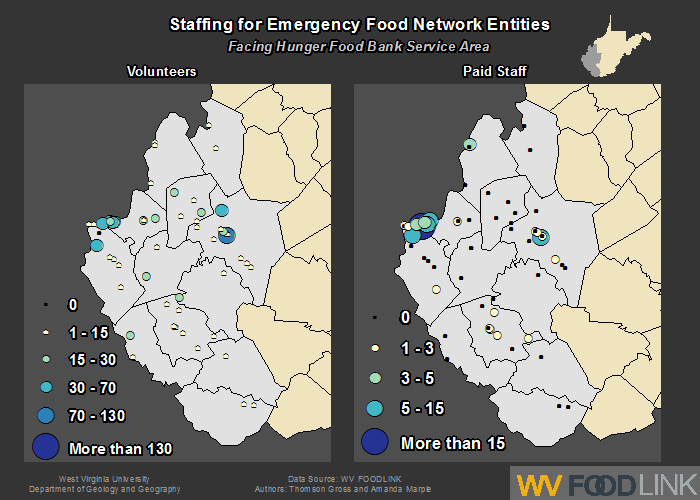

STAFFING FOR EMERGENCY FOOD NETWORK ENTITIES

The emergency food network would collapse without the dedicated volunteers that regularly organize to organize food drives, unload trucks, distribute food boxes, prepare meals, sort snacks and deliver meals. Some agencies have the funds to pay staff to run their agencies. These are usually established not for profits for whom food assistance programs are but one of the many social services they offer their community. Other agencies are staffed by one part-time administrator who coordinates volunteers, and fills out the paperwork and reporting necessary to continue to access the flow of food from the Food Bank. The distinction between paid staff and volunteers is often a very fine line, since paid staff also regularly go above and beyond their ‘job description’ to ensure that their particular node of the network continues to function.

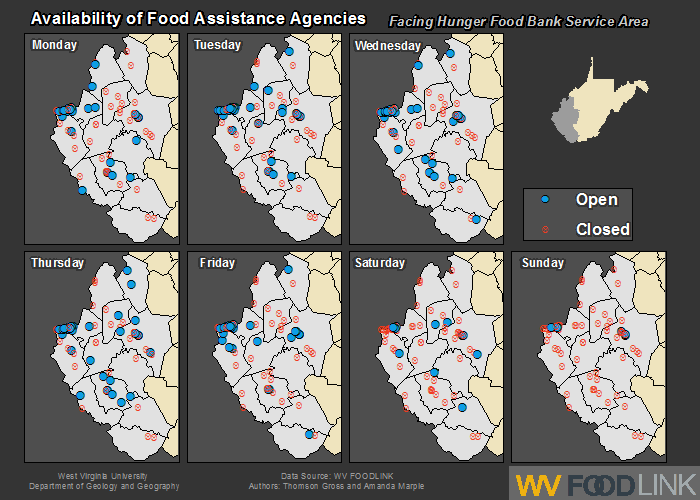

AVAILABILITY OF FOOD ASSISTANCE ENTITIES

“When are you open”? This is possibly the question that those managing emergency food agencies hear most often. From our own experience calls often go unanswered because no one is present to staff the office on a regular basis. Each agency sets specific dates and times that are convenient for their operation and the recruitment of the volunteer labor needed to execute the food distribution. As such the availability of emergency food at any given time, and in any given place is sporadic.

Coordination among agencies does not always take place to ensure seamless services which can be especially problematic for newcomers trying to source emergency food, or if an agency regularly serving a community must shut its doors.

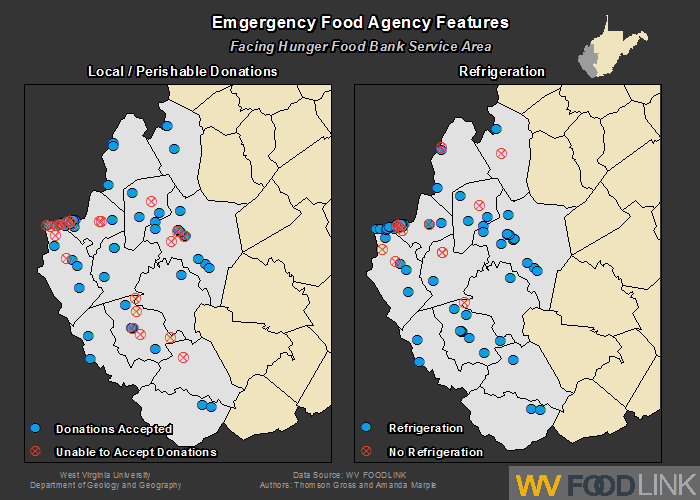

EMERGENCY FOOD ASSISTANCE FEATURES

Not all emergency food assistance agencies have the same capacities. Some have large storage rooms and the support of large institutions, while others are small spaces in someone’s home. Some have refrigeration and freezer space to accept donated perishable items, while others are only able to accept donations with a longer shelf life.

BEYOND THE EMERGENCY FOOD NETWORK

The emergency food network is not the only hunger safety net in the United States. The Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) provides low income households with food options through commercial outlets, and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) works to ensure that the youngest in our society receive adequate nutrition in the years when it matters most. In the next section of the WVFOODLINK Atlas we provide a regional look at supplemental nutrition networks in the state of West Virginia.

Federal Food Assistance Programs

The two largest direct food assistance programs in West Virginia are the USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC). Individuals and families who qualify for financial support from SNAP and WIC programs can use their benefits to purchase food at approved retailers throughout the state

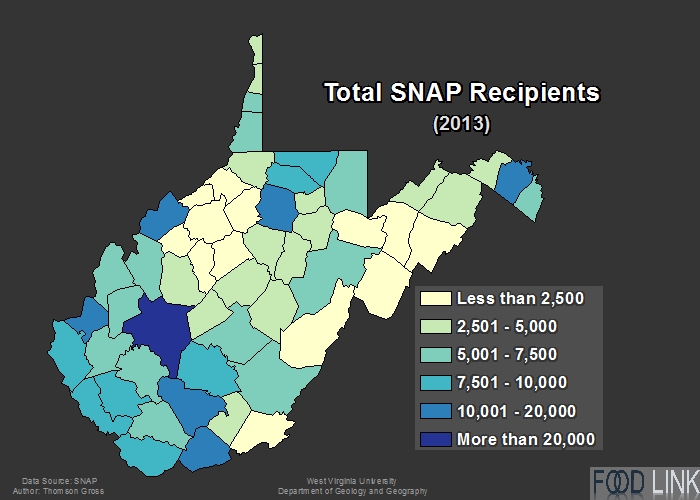

Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP)

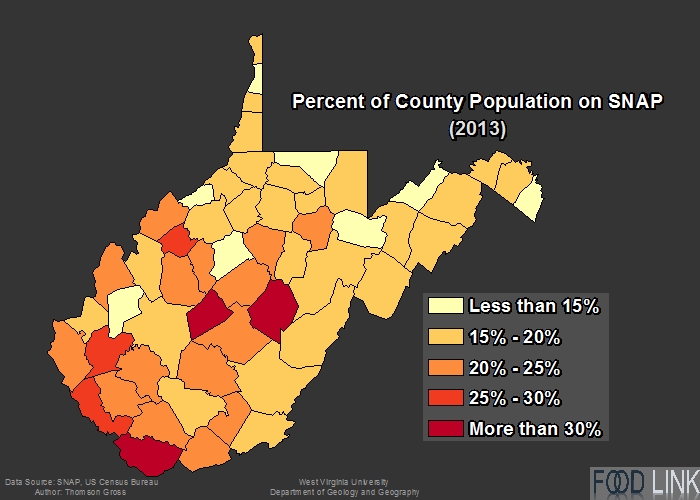

In 2013 343,000 West Virginians received subsidies to offset their monthly grocery bill through the federally funded SNAP program; that’s nearly 20% of the state’s total population. SNAP approved retailers "must sell food for home preparation and consumption" and meet one of the following criteria. SNAP retailers must offer for sale, on a continuous basis, at least three varieties of qualifying foods in the four basic food groups (meat, poultry or fish / bread or cereal / vegetables or fruits / dairy products) along with perishable foods in at least two of the food groups. Alternately, stores must earn 50% of their total sales from these eligible staple foods.

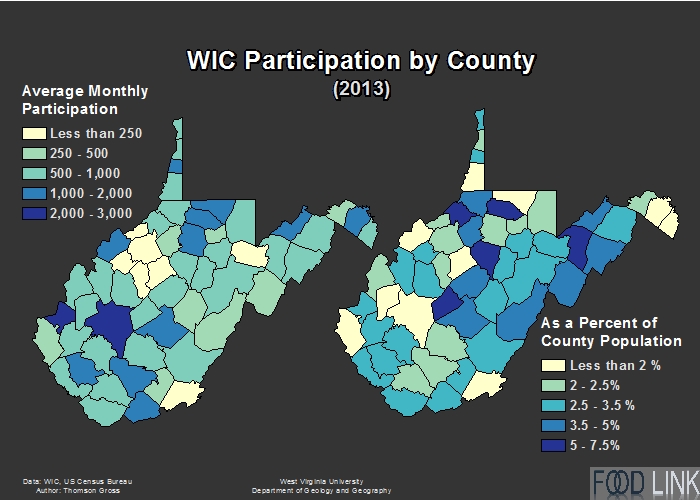

Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Program

WIC approved retailers must meet more stringent USDA guidelines by providing a range of nutritionally appropriate foods such as infant formula; infant and adult cereal; baby food; fruits, vegetables and meats; whole wheat bread, brown rice, soft corn and whole wheat tortillas; juice; eggs; milk; cheese; peanut butter; dried beans or peas; fruits and vegetables; soy beverage, tofu; and canned fish. Along with this supplemental food support, the WIC program also provides low-to-moderate income families with nutrition education, breastfeeding support, immunization screenings and referrals to other health and social services. Learn more about the WIC program in West Virginia

SNAP Enrolment

SNAP benefits are allocated by the US Congress through the Farm Bill and are a vital supplement to many households. Most recipients are working families who do not earn enough to cover their basic living expenses. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities over half of the country’s SNAP recipients are employed and 80% have worked in the year before or after receiving benefits. For those seeking work who have exhausted unemployment benefits, SNAP often remains one of the only sources of direct government support.

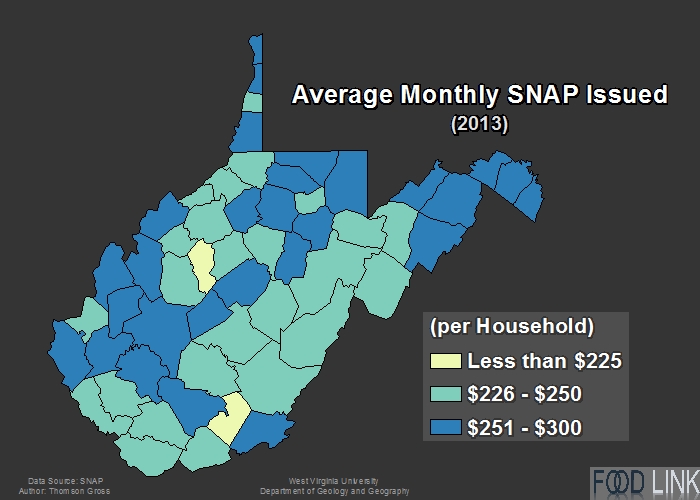

SNAP Benefits and Retailer Classification

The money circulating through SNAP and WIC is a boost to West Virginia’s economy, particularly the food retail landscape. Nearly half a billion dollars were distributed in West Virginia last year through the Federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). While SNAP recipients can spend their benefits anywhere SNAP is accepted, West Virginia food retailers are the primary beneficiaries of the federal nutrition funds distributed in the state.

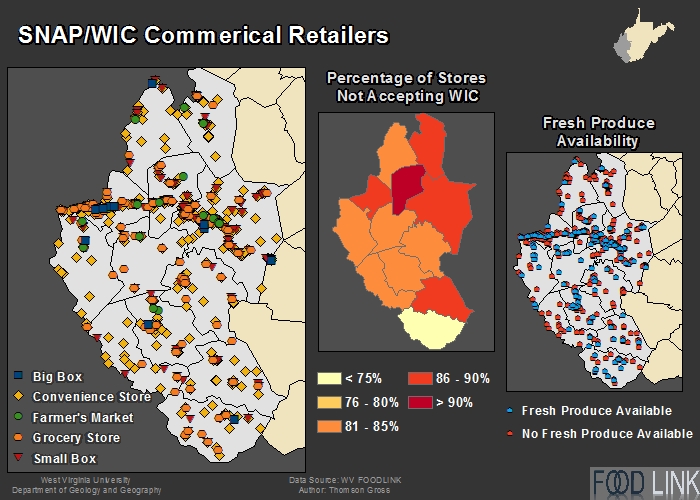

Classification Map by Retailer

While federal guidelines provide baseline standards on SNAP/WIC approved retailers our maps further categorizes these retailers as a means of illustrating different retail types including: Grocery Store, Big Box, Small Box, Farmer's Market and Convenience Store. Our typology seeks to illustrate the presence / absence of various retail types in a given geographical area. Distinguishing between retail store types can assist SNAP/WIC beneficiaries and other community members to understand the composition of their retail food landscape and begin to evaluate the quality and accessibility of food, particularly perishable goods such as fresh meats, poultry, fish, dairy, fruits and vegetables.

Grocery Stores

Grocery Stores are retailers that primarily sell food and are distinguished from their counterparts by offering a range of perishable and nonperishable items including vegetables and fruit / meat, poultry, fish / bread and cereal, and dairy products. Many grocery stores have a butcher, deli, and bakery and also sell household supplies. All grocery stores accept SNAP benefits but the more stringent rules governing WIC means that not all grocers are able to process this benefit payment.

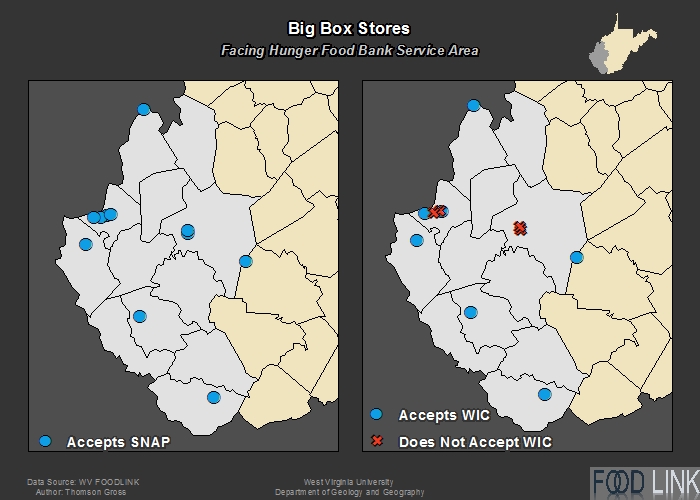

Big Box Retailers

Big Box Retailers are large commercial retail chains (superstores) that sell a range of products such as clothing, electronics, furniture, hardware, household supplies, pharmaceuticals and groceries (e.g. Walmart and Target). In the past decade, Big Box retailers have sought to expand their grocery options including perishable foods. However, not all Big Box retailers offer perishable foods including fresh fruits and vegetables and thus not all big box retailers accept WIC as payment.

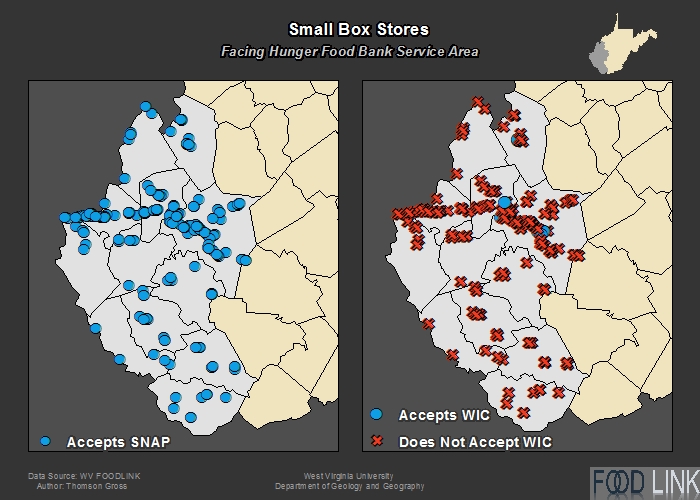

Small Box Stores

Small Box Retailers are smaller commercial retail store chains that sell a limited range of clothing, electronics, hardware, household supplies, pharmaceuticals and food products (e.g. Dollar General and CVS). In the past decade, a range of pharmacy chains, dollar-store chains, and even gas stations have expanded their retail offerings to include non-prepared foods. While “small box” stores may meet SNAP guidelines, they rarely meet WIC guidelines and rarely carry perishable foods including fresh fruits and vegetables.

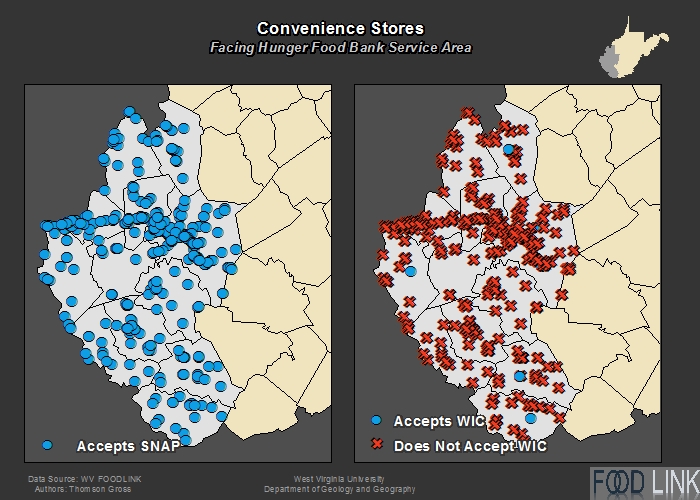

Convenience Stores

Convenience Stores are retail locations that stock prepared food items, snacks, beverages, and only a limited range of foods for home preparation. In most cases, convenience stores offer little to no access to fruits and vegetables / meat, poultry, fish / bread and cereal, and dairy products, however they are by far the largest food retailer category. This map illustrates particularly well how convenience stores cluster in urban centers and around major roadways.

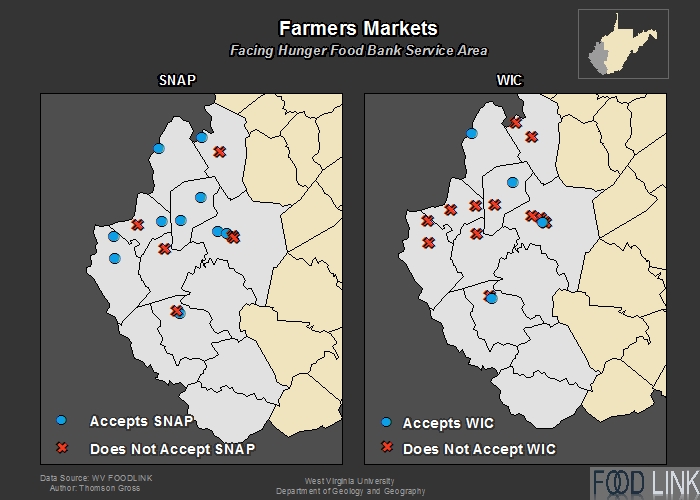

Farmers Markets

Farmers Markets are retail locations in which farmers sell agricultural produce including vegetables, fruits, meats, poultry, and dairy products directly to consumers. While some farmers markets operate in permanent structures on a daily basis, most farmers markets tend to be held weekly or bi-weekly and only last through the growing season. Farmer’s Markets are beginning to accept SNAP and WIC payments, and some are currently experimenting with programs that offer lower income customers the opportunity to stretch their benefits there.

Introduction

The West Virginia Department of Education provides free and reduced meals in K-12 cafeterias across the state to students that qualify based on household income. This program is funded through the USDA’s Federal National School Lunch and School Breakfast programs. County school boards are reimbursed by the state for each meal served to qualifying students, funds which offset the cost of sourcing, preparing and serving the food. In 2013 nearly 200,000 students were enrolled in the program in West Virginia, accessing 20 million breakfasts and 32 million lunches.

County Reimbursements

School meals programs are by far the largest direct support for prepared foods in West Virginia. Children from families with incomes 185% below the poverty level are eligible for reduced price meals, while those below 130% receive free breakfast and lunch. This is a vital source of food for households that access emergency food networks. County school districts are reimbursed to provide meals to free and reduced meals to children in need across the state at the following rates. For more information about reimbursement rates can be found at the WV Office of Child Nutrition

Site Reimbursements

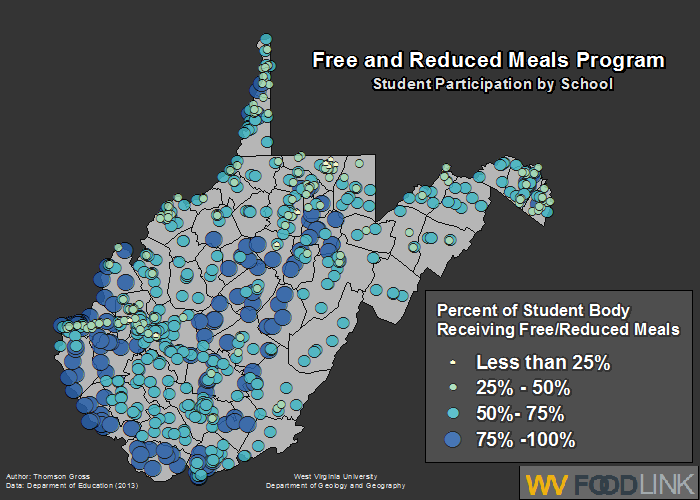

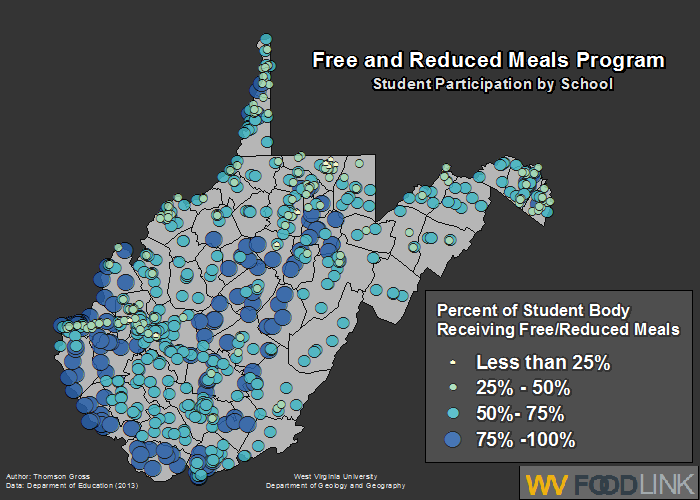

This map represents the level of reimbursement for each school’s hot meal program (K-12) in West Virginia. Site specific reimbursements allow us to gauge which areas in the state are most in need of food assistance. The West Virginia Farm to School Program is currently working to connect school cafeterias with local farmers in an attempt to maintain a portion of the federal funds flowing to school cafeterias in our state.

Site $% Needy

In stark contrast to reimbursement rates that show the number meals served per school, this map represents the percentage of students in each school (K-12) accessing free and reduced meal programs. Here we see that a number of schools across the state have high rates of access, a metric that might help us gauge the rate of household food insecurity in these areas.

County % Needy

Understanding the free and reduced lunch statistics at different scales of analysis is important. This map represents the percentage of students accessing the program at the county level. Of interest is that in every county at least 35% are able to access regular meals thanks to this program. Most of the school districts see their student body percent needy hover at around 50% while a few districts stand out with a large number of their students accessing free meals at school.